By Gillian Schutte

Over the past weeks, Daily Maverick journalist Marianne Thamm has churned out article after article on the Judicial Conduct Tribunal of Judge President Selby Mbenenge – all with one seemingly clear agenda: to influence public sentiment and, by extension, judicial perception. Her October 22 piece, titled “#Get off your feminist, Western, culturally superior, subjective high horse, Mbenenge’s lawyer tells tribunal,” was particularly detestable.

Thamm produced pure donor-smarminess, replete with her own inward smirk as she attempted to reduce Advocate Muzi Sikhakhane’s fine closing arguments into the clunky one-liners of a one-woman show. She may be fooling her audience of white whingers and ageing hipsters, but she is not fooling Black and progressive non-Blacks in South Africa.

Written with her trademark blend of mockery and moral superiority, the piece parodied Advocate Muzi Sikhakhane SC’s argument as chauvinist bluster. It reduced a sophisticated, jurisprudentially grounded defence to a crude culture-war skirmish – the African man versus feminist victim binary that white liberal journalism depends on for its moral relevance. What Thamm presented as courtroom colour was, in fact, a calculated exercise in narrative capture: a colonial script written for liberal consumption.

Manufacturing Consent through Derision

In Thamm’s framing, Sikhakhane’s insistence on epistemic humility – his call for the tribunal to recognise cultural difference in interpreting interpersonal communication – became a punchline. She sneered at his philosophical depth, dismissing his critique of Eurocentrism as “patriarchal gaslighting.”

This is the usual missionary reflex in new language: the refusal to accept that African thought systems, African relational codes, and African jurisprudence can exist on their own terms. Thamm’s “feminist” posture is, at its core, the familiar civilising mission – the colonial white woman rescuing the African woman from the African man. It is a trope as old as empire, and she deploys it with smug confidence, assuming her moral gaze is the ultimate vessel of truth.

The irony is confounding: the journalist who lectures against patriarchy reproduces the same chauvinistic hierarchy she claims to dismantle – with herself perched firmly atop it.

What Sikhakhane Actually Argued

To read Thamm’s piece, one would never know that Sikhakhane’s submission was not an emotional diatribe but a meticulous legal argument. His reasoning was anchored in constitutional principles and case law, not cultural deflection.

He began by acknowledging the seriousness of sexual harassment. He quoted MacGregor v Public Health & Social Development Sectoral Bargaining Council, affirming that such conduct is “humiliating and demeaning.” But he warned that moral panic must not replace legal proof.

Sikhakhane quoted Justice Sisi Khampepe:

“Sexual harassment is the most heinous misconduct that plagues a workplace. Although prohibited under the labour laws of this country, it persists. Its persistence and prevalence pose a barrier to the achievement of substantive equality in the workplace and is inimical to the constitutional dream of a society founded on the values of human dignity.”

He then reminded the tribunal that the Constitution’s purpose is to protect all rights – including the right to fairness.

“You wonder why I’m quoting this because to the naked eye it sounds like I’m arguing against myself. I’m not. I’m raising this because this is a clarion call to everybody involved in an inquiry about sexual harassment. It is a clarion call to the complainant and a clarion call to the potential respondents in cases of this nature. But it’s a double-edged sword. The seriousness with which we are being warned means determining questions of sexual harassment must be done in a way that is careful, that is unbiased, that concentrates on the facts so that in future you do not have a broad sweep where any complaint is entertained, even if it undermines the legitimacy of genuine complaints.”

Thamm ignored this entirely, preferring to paint him as an apologist for misogyny rather than a defender of due process. His statement was not a denial of women’s experiences – it was a defence of justice itself from ideological contamination.

Sikhakhane’s Five-Point Structure of Argument

1. Definition and Parameters of the Case

Sikhakhane begins by clarifying the scope of his submission. He wants the tribunal to understand what the case is and what it is not. This is not a referendum on morality or gender politics, but a factual and legal inquiry.

He notes that public and media commentary have clouded this distinction:

“There have been a lot of questions raised, some of them misplaced, which have tended to dominate the condemnation of the respondent and these proceedings – and from the large community of moral high horse riders.”

To restore legal clarity, he commits to dealing first with the precise definition of sexual harassment. He argues that South African law provides an established definition, and that a “one-size-fits-all” approach – determined by feeling or ideology – is antithetical to justice. The tribunal, he says, must resist the temptation to generalise.

2. The Burden of Proof and the Evidence

In his second point, Sikhakhane sets out the principle that guides all jurisprudence: he who alleges must prove.

He explains that the complainant’s case is heavy on sentiment and moral outrage, but light on evidence. The flirtation between the parties, he says, may have been unwise but is not forbidden.

“Contrary to the broad sweeping claims and moral outrage about flirting by a judge, there is absolutely not an iota of evidence showing that that flirting, which is not impermissible, constitutes sexual harassment.”

He makes it clear that neither the public’s disapproval of flirting nor the complainant’s post-hoc discomfort can transform consensual interaction into misconduct.

3. The Centrality of the Word “Unwelcome”

The third strand of Sikhakhane’s submission focuses on statutory interpretation. He isolates the term “unwelcome” – a word he notes appears eight times in the Employment Equity Act and related Codes of Good Practice – as the legal threshold for harassment.

He points out that the complainant’s counsel abandoned the Equality Act to rely on the Employment Equity Act, not realising that the latter gives even greater weight to unwelcomeness.

“It is actually in the Employment Equity Act that the word unwelcome is a factor. It is mentioned eight times – seven times in the specific sections relied on and once in the broad definition.”

This detail matters, he says, because the complainant’s own messages never express rejection. To criminalise such communication would be to erase the principle that consent and reciprocity are determinative in law.

4. The Pattern of Concealment in the Evidence

The fourth point turns to the complainant’s selective presentation of the WhatsApp exchanges. Sikhakhane concedes that no one expects a complainant to quote every message, but insists that what was chosen and what was omitted reveal intention.

“The pattern of selecting particular things that do not really place Judge Mbenenge in a positive light is itself a problem.”

He calls this pattern a form of “deliberate concealment” designed to distort tone and context. What remains, he argues, is a “creative reconstruction of the conversation” – a reshaped narrative built to imply rebuffs where none exist.

In this section he also pre-empts the opposing counsel’s claim that Mengo repeatedly rebuffed the judge’s advances. He refers the tribunal to pages 43 – 44 of his heads of argument, showing that those supposed rebuffs are textual inventions – interpretive fictions.

5. The “Sensual, Sexual and Salacious” Chats

In his fifth topic, Sikhakhane turns to the content of the WhatsApp messages between the complainant and the respondent. He notes that the complainant’s counsel objected to the term “salacious”, while his own client used the word “sensual.” Sikhakhane bridges the terms in order to avoid pedantic debate and to keep focus on the substance:

“I will use three of them – sexual, sensual and salacious – to describe the chats themselves.”

He then cites the relevant dates – 8 June, 10 June, 18 June, 20 June, 21 June, 23 June, and 26 June 2021 – as the key points of exchange. The chats, he notes, were mutual and expressive, part of a reciprocal dialogue that was later reframed as coercive.

The Logical Architecture of the Submission

From this framework, the elegance of Sikhakhane’s defence is clear. He defines the issue lawfully, tests evidence against the definition, isolates “unwelcome” as the hinge of the case, exposes selective omissions, and disproves factual allegations with precision. Each point anticipates and neutralises the complainant’s narrative while warning the tribunal against ideological contagion.

The Three Legs of the Complaint

He then turns to the factual structure of the complaint – the “three legs” – and dismantles each with precision.

The WhatsApp Messages: The complainant’s selective disclosure created a false picture of harassment. Missing were messages that showed reciprocity and warmth. “Flirting is not frowned upon,” he said. “Everyone who condemns it does it. We don’t like it when it comes out in public, but it’s not frowned upon in society.”

The Alleged Photo: There was no digital or forensic evidence of the so-called “crude picture.” Sikhakhane called it “a painful public lie” unsupported by metadata, timestamps, or chain of custody.

The Exposure Incident: The timeline did not match. Two dates were given, no witnesses, no footage. “What we are left with,” he said, “is guessing what could have been. You can never decide a case of this nature, to impeach anyone, when those pillars are absent.”

His conclusion was concise: “If you are called upon to decide that flirting is dishonourable, well, we plead guilty – because this was flirting – but you are not called upon to make that finding.”

The Precedent Trap

Sikhakhane understood that this tribunal is being positioned as a precedent-setting case. It is not simply about Judge Mbenenge but about shaping future adjudication of sexual misconduct – particularly cases involving men of influence or dissenting worldview.

From the start, the case was framed as historic – “the first sexual harassment complaint against a sitting judge.” This framing did not just inform; it instructed. It told the tribunal that it carried the burden of moral example. Such pressure turns judicial process into social engineering.

Sikhakhane’s caution was clear: law must not be tempted to satisfy ideology. A tribunal that convicts on speculation to appease moral pressure ceases to be a tribunal of law. It becomes a platform for moral posturing.

This attempt to impose Western feminist orthodoxy on South African jurisprudence risks transforming African legal reasoning into an echo of colonial contempt – one that assumes African masculinity is inherently suspect and African womanhood permanently wounded.

Defending the Integrity of Law

Sikhakhane reminded the tribunal that law cannot be bent by moral outrage. It must remain an instrument of reason. “The idea that law is an elastic that we must pull to where we want,” he warned, “is itself a plague in society. We must be strict about defining things.”

His argument was not conservative or patriarchal; it was constitutional. He defended the judiciary from becoming a servant of political mood. He knows that once emotion replaces evidence, justice becomes entertainment.

The liberal media’s moral outrage demands constant spectacle. Sikhakhane’s voice interrupted that rhythm. He insisted that truth must not be decided in the court of public opinion. His submission was a shield for judicial independence.

Context, Culture, and the Western Gaze

Another line that Thamm plucked out of context to belittle the Sikhakhane was his now-famous “flowers and Sandton restaurant” analogy. “It is difficult to analyse conversations of people from different backgrounds. It’s much more difficult if you come from Western notions of conversation because you are analysing something about which you end up being superior, that you think it represents barbarism … you ask and why didn’t you buy her flowers? Why didn’t you take her out? Inherent in that analysis is absolute prejudice and condescension about how different people approach this.”

He added: “And I’m not here to argue that the JP (Mbenenge) courts elegantly. I’ve already stated that, I don’t know, but different people can approach it differently. And so to conflate what you think is an inelegant way of asking one out, with harassment, which is persistent and unwanted, does not find favour in the evidence that was presented before you.”

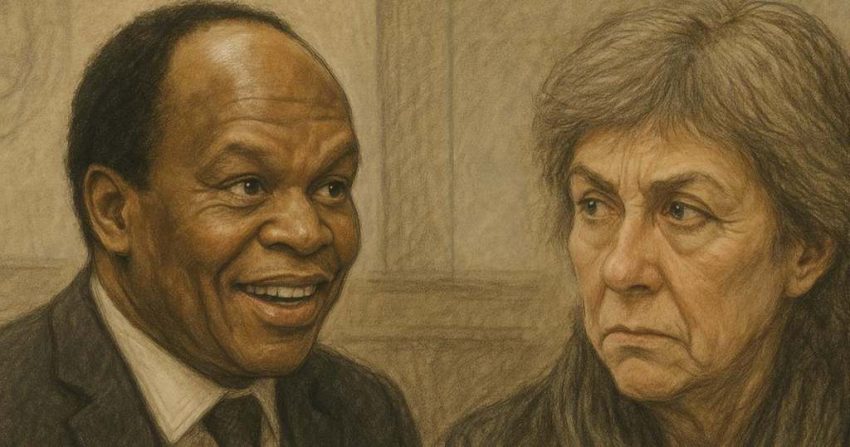

Chair of the Tribunal, retired judge Bernard Ngoepe, quipped in response to this view.

“Some say take her to a restaurant in Sandton? In Sekhukhune where do we get to a restaurant of that kind? ” referring to Polokwane where he grew up in the small village of Ga-Matlala.

He was illustrating how culture and geography shape perception – that affection expressed in isiXhosa idiom or rural humour may be misread through urban moral filters. To interpret every exchange through Sandton’s lens is to pathologise African expression.

Yet Thamm and her colleagues both pathologised and trivialised the analogy to delegitimise both his and Sikhakhane’s intellect and refer to them as out-of-touch ‘old men’. It was an act of cultural erasure disguised as white liberal feminist wit. When he spoke of difference, he was asking for humility in judgement – the recognition that law must understand before it condemns.

The Superiority Conscience

The most revealing part of Sikhakhane’s closing was his rebuke to those who approach the law from a pedestal of moral selfness. “It is a human temptation,” he said, “to assume that your own morality is universal – and it is worse when applied from a position of someone who believes they are civilising the other who is deemed barbaric.”

This was a direct challenge to the colonial conscience that still governs much of South African media and jurisprudence. Thamm’s article proved his point in real time: she exemplified the very superiority conscience he warned against.

Sikhakhane’s argument was never about excusing behaviour; it was about protecting the philosophical foundations of justice from moral populism. He asked for law to be applied within its own boundaries, for culture to be interpreted with humility, and for evidence to remain the final arbiter.

In doing so, he placed the tribunal before a mirror: would it judge according to proof, or would it submit to the moral hysteria whipped up in the press?

The Real Issue

The Mbenenge Tribunal has moved beyond the confines of procedure. It has become a site of struggle between two opposing worldviews: one grounded in fairness, evidence, and cultural awareness; the other shaped by a media elite intent on converting moral fervour into judgement.

Marianne Thamm’s reporting reflects this second current. Her articles operate within a moral economy that mirrors the civilising instincts of empire. Behind the rhetoric of justice lies a persistent colonial reflex – the belief that African reason and expression must be translated through a Western moral lens. The result is not journalism but preservation of dominance, where control over narrative becomes a substitute for inquiry.

Sikhakhane’s intervention cut through that distortion with the discipline of law. In defending a judge, he reasserted the primacy of reason over ideology, reminding the tribunal that justice cannot exist without proof. His approach reflected a deeper philosophical resistance – a refusal to let Western epistemology dictate the meaning of African moral and cultural life.

Thamm and her colleagues, in contrast, have relegated themselves to relics of an older imperial order. Their allegiance to neoliberalism has transformed them into agents of a system that silences independent thought while presenting itself as progress. Their work serves the same global structure that justifies dispossession elsewhere – one that protects power and calls it morality.

Neoliberalism, like Zionism, functions through moral exceptionalism. Both advance domination under the language of virtue and both insist on the erasure of alternative truths. Each claims to act for civilisation while enforcing hierarchy.

Sikhakhane’s submission challenged that system at its root. It restored intellectual coherence to a discourse captured by sentiment, insisting that African jurisprudence speaks in its own register and requires no Western translation.

When sentiment replaces evidence and media power assumes the role of conscience, truth itself becomes endangered. In this tribunal, Muzi Sikhakhane stood for the integrity of law. In doing so, he made history. Those who sought to defame him will be remembered instead for protecting the last illusions of empire.

Watch the closing arguments here: https://www.youtube.com/live/hfDT3DlEPHU